For Pedro Loredo (MDes 2023), design is collaborative, human-centered, and open to all types of art and craft. Growing up in Mexico City, Pedro always knew he wanted to do something creative, but he was expected to work within the parameters of the public education system. He was interested in fashion design, but that was not part of the system.

Instead, he studied integral design at EDINBA (Escuela de Diseño del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes). This program integrated graphic design, textile design, and industrial design. He joined a community of fashion designers to create collections, and runway shows alongside his degree.

“We came up with our own fashion course and we called it ‘experimental fashion.’ Our main goal was to make fashion in collaboration—everything was designed by everyone. Our first project was to look at the future of fashion. We designed a collection that was speculative. What fashion trends will people wear at certain times in the future?” says Pedro.

“The first one was the apocalypse. Back in 2011 or 2012, there was a lot of talk about the end of the world. We took that and came up with a bunch of designs for the end of the world. It’s sort of like a festival and a fashion show, but it’s not part of the curriculum.”

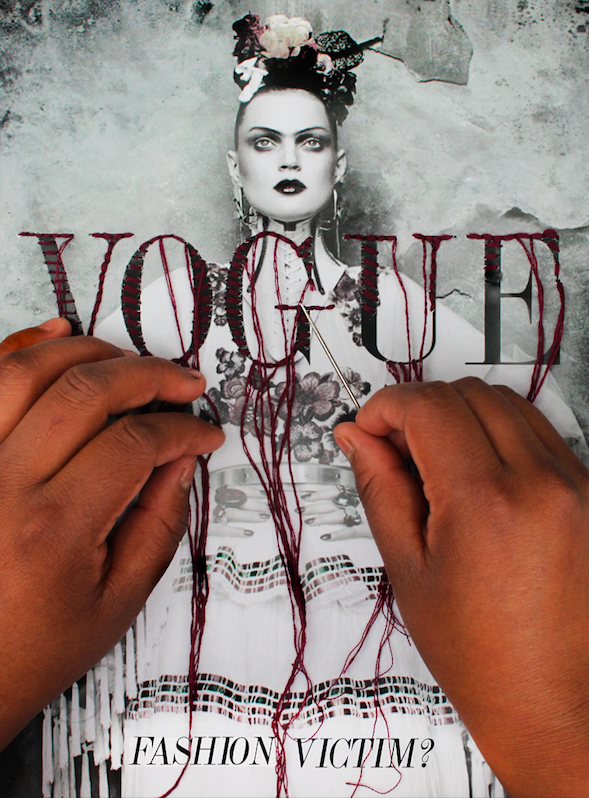

EXPERIMENTAL FASHION

As part of the experimental fashion series, Pedro designed a line of accessories. The brand was called UNEVEN and the tagline was ‘unconventional structures.’

“I was given the chance to do a runway collection. It wasn’t going to be ready to wear. It was very sculptural. It was made of recycled materials, like a cable hose. It was primed with epoxy. I painted the pieces, and they became wearable sculptures,” he says.

Pedro’s accessory line was featured in NYLON Magazine. He got lots of positive feedback on his designs but still couldn’t convince his mother that kind of fashion design was the right path.

“It was popular when it showed in the magazine, but my mother said, ‘I can’t see myself wearing this.’ I was like, ‘Mom, this isn’t for you to go to the supermarket. This is different.’ She didn’t understand why I was asking her for all this money since it wasn’t for school.”

The collection didn’t go any further. Pedro explained it was too difficult to get the collection made into a ready-to-wear pieces. It was too experimental at the time.

After his undergraduate degree, Pedro spent a year in Montreal before returning to Mexico City to work at an event marketing agency. At the agency, he worked on a lot of commercial conferences and corporate events, but he remembers winning the pitch to promote an event at a well-known museum in the city, Casa Risco.

The client wanted the exhibition to be based on the pre-Hispanic Mexica legend of ‘El Mictlan,’ which is very similar to Dante’s Nine Circles of Hell. The exhibition coincided with the Day of the Dead.

“My idea was to bring to life Dante’s 9 Circles of Hell. It’s about what the soul must do to get to paradise. We built furniture and took over an entire wing of the museum, with a central patio. The challenge was to make it immersive without it looking like a high school production,” he laughed.

‘El Mictlan’ exhibition in Museo Casa del Risco, Mexico City. Courtesy: Pedro Loredo.

COMING TO NSCAD

Around that time, Pedro attended a university fair and came across the NSCAD University booth. It was the only university that had a Spanish-speaking representative. Although he’d never heard of the university, or Halifax, Pedro applied and was accepted for his master’s in design. He started his program during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I started the program from Mexico and my entire class was based in their home countries. Design needs collaboration but everyone was in different time zones, so we had to cover off for each other. We each took shifts, because when I was awake, my classmate in China was not. We would do the readings, and we had to discuss what we thought and what it meant. It was truly collaborative because we had to figure out ways to work together across geography and time zones.”

When Pedro finally came to Halifax, it was during the days of the “Atlantic Bubble,” when the Atlantic provinces mandated everyone entering the region to quarantine in order to curb the spread of COVID. His tutor wrote a special letter to get him into the province, and he was quarantined in a hotel for two weeks. He has lived in Halifax ever since.

“I was well into my degree when I saw NSCAD for the first time. I knew what it looked like from the pictures, but I got a real sense of the buildings and the history between the walls. I fell in love with the university and the city of Halifax”

Pedro really appreciated NSCAD’s unique approach to design.

“NSCAD encourages you to look at your creative practice from a personal perspective. In Latin America we were taught that you cannot be a parameter for what you design, but NSCAD encouraged me to design from my own lived experiences. It’s called autoethnography.”

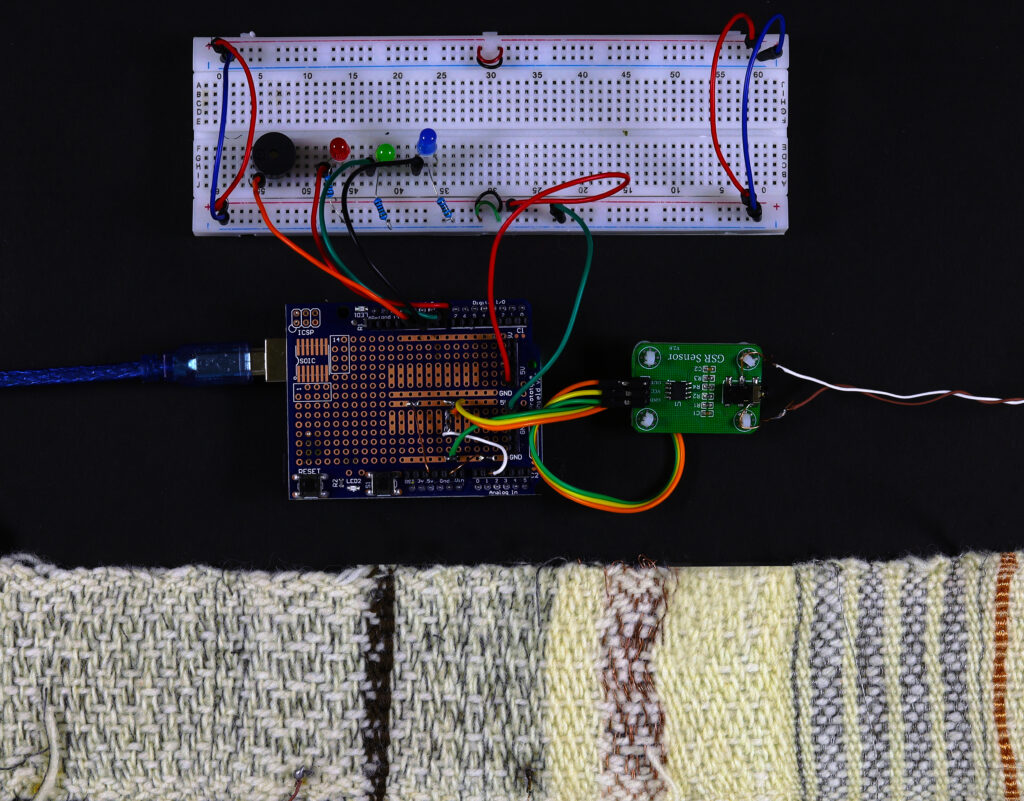

SMART TEXTILES AS A TOOL FOR THERAPY

Around that time Pedro was diagnosed with ADHD. He realized that one of his biggest struggles was communicating with the people around him when he needed to focus.

“I went, ‘OK what is something that I really struggle when I come into the studio?’ I’m coming to the studio to do my homework, my project, and everything. I don’t want to talk to people. I don’t want to be interrupted. If only these people knew when I was in the mood to be social.”

In researching his own condition, Pedro learned that people with ADHD and on the spectrum have trouble recognizing emotions and understanding expressions. At first, he tried to design a mood ring, but that had already been done.

“I was working with textiles, so it made sense to do a version of the mood ring in that medium. I knew that a lot of people with autism have wearability triggers, but generally, they have to wear clothes (unless they just can’t), so why don’t we embed sensors in the clothing?”

Pedro went on to examine how textile design can help with emotional management and enable preventive interventions for people with autism. His thesis focused on the potential of ‘smart textiles’ as a non-invasive therapeutic tool. He came up with a prototype that integrates a microcontroller and a four-frame loom to create woven textiles that can sense when a meltdown is developing.

“Design can be integrated into anything, whether it’s clothing, buildings, streetscapes or video games. It’s about helping people make the most of their day-to-day lives,” he says.

He is currently working alongside a neuroscience and psychology professor who is exploring EEG, or electroencephalography, as a tool to create video games for people with mobility issues or who are missing extremities.

From experimental fashion for the future, to creating ‘smart textiles’ that can detect meltdowns, Pedro Loredo is ahead of his time when it comes to design and wearable art.