Dr. Vajdon Sohaili, Assistant Professor in the Division of Art History, is launching a new course exploring the history of architectural destruction in global crisis—including war, climate change, and housing insecurity. Titled, Architecture and Crisis (AHIS 4270), the course is a culmination of Sohaili’s ongoing research into the concept of “contemporary reconstruction.”

To learn more about the ideas behind the course and the significance of this work in today’s shifting geo-political landscape, fellow Art History faculty member and Division Chair, Dr. Karin Cope, sat down with Sohaili for a Q&A.

Karin Cope: What themes do you plan to think about in this course?

Vajdon Sohaili: War, statelessness, climate emergency, colonialism, unhousing, etc. We’ll consider these themes through a cross-section of historical case studies taken from around the world, as well as from our own city.

We’ll also look at some ways that artists, curators, and activists have used architecture to highlight crisis and activate resistance. For example, we’ll look at the hypermediation of 9/11 and the expansion of U.S. aggression; the detonation of Pruitt-Igoe in 1972 and the public housing crisis that it fueled; the erasure of entire cities in China to accommodate the world’s largest dam; and the systematization of concentration camps as a means of managing statelessness (think Auschwitz to the so-called “Calais Jungle” to CECOT).

We’ll look at Halifax—including a visit to the Halifax Municipal Archives—and think about the numerous cases of appropriation, displacement, and post-calamitous reconstruction that mark its history; as well as the ongoing crisis of housing and education that I suspect students will connect to in very personal ways. We’ll also consider some key examples of creative intervention that use architectural thinking—Hans Haacke, Haroun Farocki, Forensic Architecture, Namibia’s Nest Collective, the films of Ameen Nayfeh and Jonathan Glazer—including the upcoming exhibition at the Dalhousie Art Gallery, “Regarding Land,” curated by Amin Alsaden, who will also be talking to the class.

But I’m not interested in students “knowing” about historical examples or demonstrating some kind of disciplinary mastery over architecture. I’m much more interested in the ideas that will be sparked, connections made, and conversations generated through some of these examples. We all live in and alongside architecture every minute of every day; we are its intended users and audience. As artists and art historians, we’re also deeply invested in making and in thinking about the effects of what we make. And I’m assuming we’re all concerned humans who would like to make the world a better place. These are the main prerequisites!

I’m hoping the course will offer a forum for students to think about their own personal relationships with the world and to issues they care about, using the built environment as a lens to do so. The final project assignment will allow students to develop these ideas into an original work of creative expression. We will work incrementally on these projects throughout the course, presenting them in a class-curated group show at the end of the semester.

KC: What key questions come to mind when you talk about architecture and crisis?

VS: Walter Benjamin said that architecture is “received in a state of distraction.” I understand this to mean that architecture is ubiquitous and yet somehow presents to us as neutral, or subordinate to practical or functional concerns. I’m interested in this idea of distraction. What are we being distracted from? Is architecture doing something other than what we expect? And is there, perhaps, something about crisis that “wakes us up” from distraction? If we look at it undistractedly—with a critical eye, a crisis-eye, what can architecture tell us about the environments it shapes?

Here, I’m speaking of environments as social, political, ideological, ecological, and semiotic concepts, as well as designed and built. I’m also speaking broadly about architecture to include things like space, design, landscape, hidden architecture—things replaced by buildings or left behind after they’re demolished.

Importantly, for this class, I want us to explore how visual artists and curators might use this critical awareness/awakeness: how could architecture operate as a “way in” for creative work that challenges the injustices and hypocrisies embedded in those environments?

KC: Why architecture? How does it enable us to think about specific kinds of historical and contemporary events and problems? Put another way, How does it sit in relationship to what we call “art history”?

VS: It’s a bit of cliché to say that “architecture is entangled with power”—but the shoe fits! The vast majority of buildings cannot be achieved without financial, legal, and political compliance, and those same systems structurally withhold the benefits of architecture from the most vulnerable.

In situations of crisis, we see architecture operating multi-laterally: a symbolic victim, an expression of power, even a kind of cover-up, or—to be less conspiratorial—a measure for mitigating and perhaps redirecting public condemnation. Of course, architecture is frequently recruited to remedy injustice, but even there, it too often re-brutalizes, re-marginalizes, re-erases. The point is architecture is rarely an explicit tool of power; it is, rather, a complex, multidimensional field over which forces of oppression and progress negotiate.

In terms of art history, I think of architecture as having a borderline ontology: between art and utility, form and function, façade and plan. Similarly, in sociopolitical terms, it splits ground between land and use, policy and practice, profit and service. But architecture (unlike visual art) is more than just an index or a record of history, it’s often at the driving core of major and problematic events like colonialism, incarceration, climate change, and unchecked capitalism. Yet despite all this, architecture has this quality, suggested by Benjamin, of being hyper visible yet oddly unnoticed or under-examined.

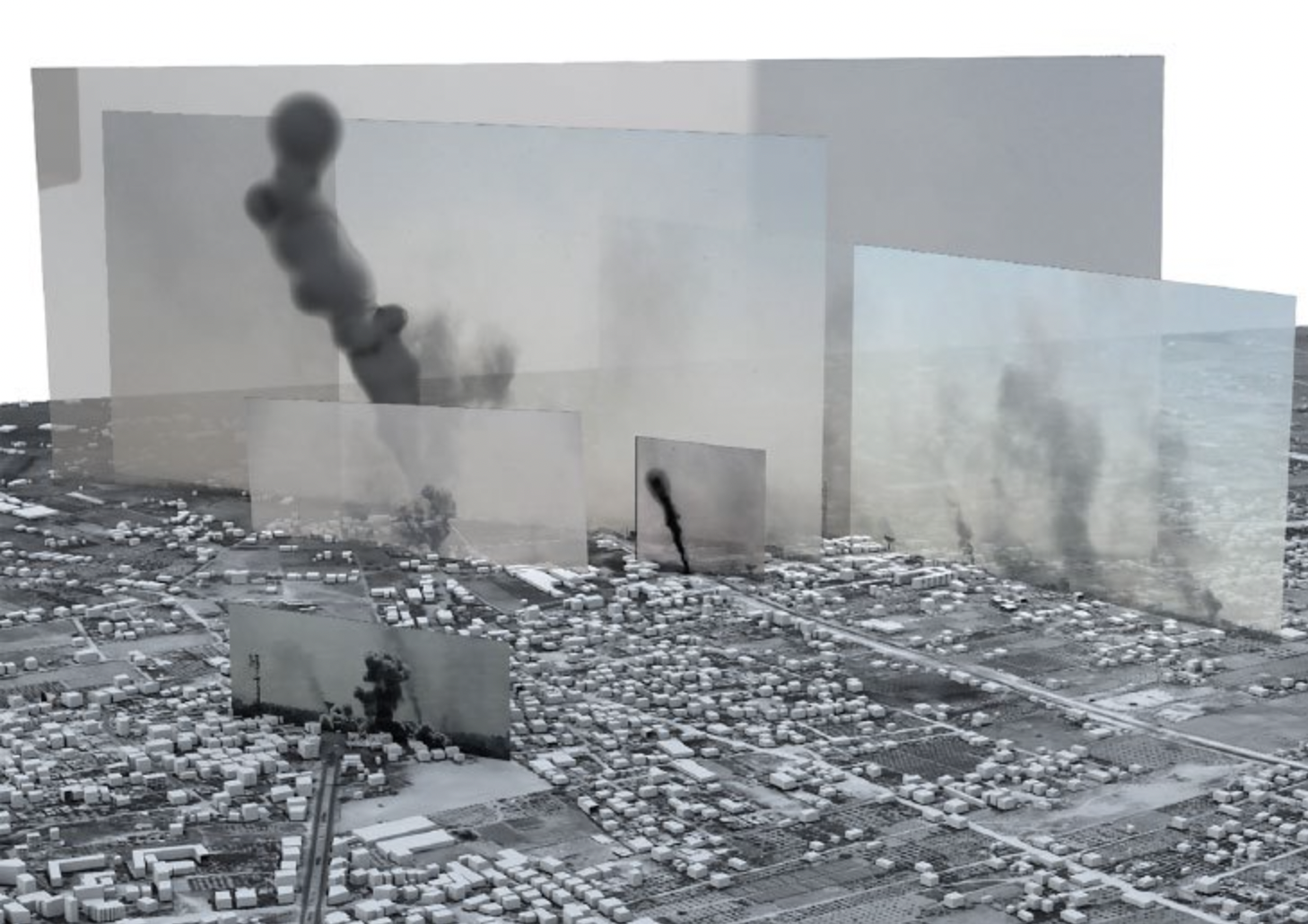

As a lens, architecture is very dynamic and intersectional; it offers neutrality, new perspectives, new permissions. It allows, for example, an architectural critic like Edwin Heathcote to speak about the war in Gaza as “urbicide”—the killing of cities—rather than “genocide,” and thereby evade the corporate editorial censorship of the publications for which he writes, while also clearly invoking the undeniable crime against humanity taking place.

KC: What about crisis? I remember when I was a student in the 1980s, both “crisis” and “terrorism” were key points of political division and discussion. It seems like they are back—or perhaps they never left. Is crisis a more urgent question now than it was five years ago? If so, why?

VS: Whether or not we subscribe to a crisis theory, what seems clear is that power has been using crisis or the threat of crisis for a long time to push through increasingly oppressive agendas. More than ever, our world is being shaped by crisis-thinking. Rather than try to separate out what’s a crisis or when, I’m interested in recognizing how crisis-control has become the pervasive methodology of our time.

To this end, architecture is a rich object: building design is unusually allergic to crisis—it wants to bring shape, order and solution. So, when a building fails or falls, we get a valuable glimpse, not only into the crisis that caused its failure, but also into the crisis-thinking that put it there in the first place, and that will replace it, supposedly improved.

I will say, also, that crisis can be very personal, especially for an artist. While much of the course will look to historical or societal crises, I hope students will feel inspired to explore the way crisis and crisis-thinking shapes individual experience and domestic space. In my view, the ability to move between local and global, between microcosm and macrocosm, is an artist’s greatest superpower.

One more thing about crisis and ‘emergency’—which was an alternative concept when I was planning this course—is that they both keep very good company, etymologically speaking! “Crisis” for me is a call to “critique,” to see critically. Similarly, “emergency” always also entails “emergence,” an opportunity to see with a new clarity, things that were previously clouded. So, “Architecture and Crisis,” I hope, serves not only as a history, but also a method.

KC: Do you want to talk about the relationship between rubble and history?

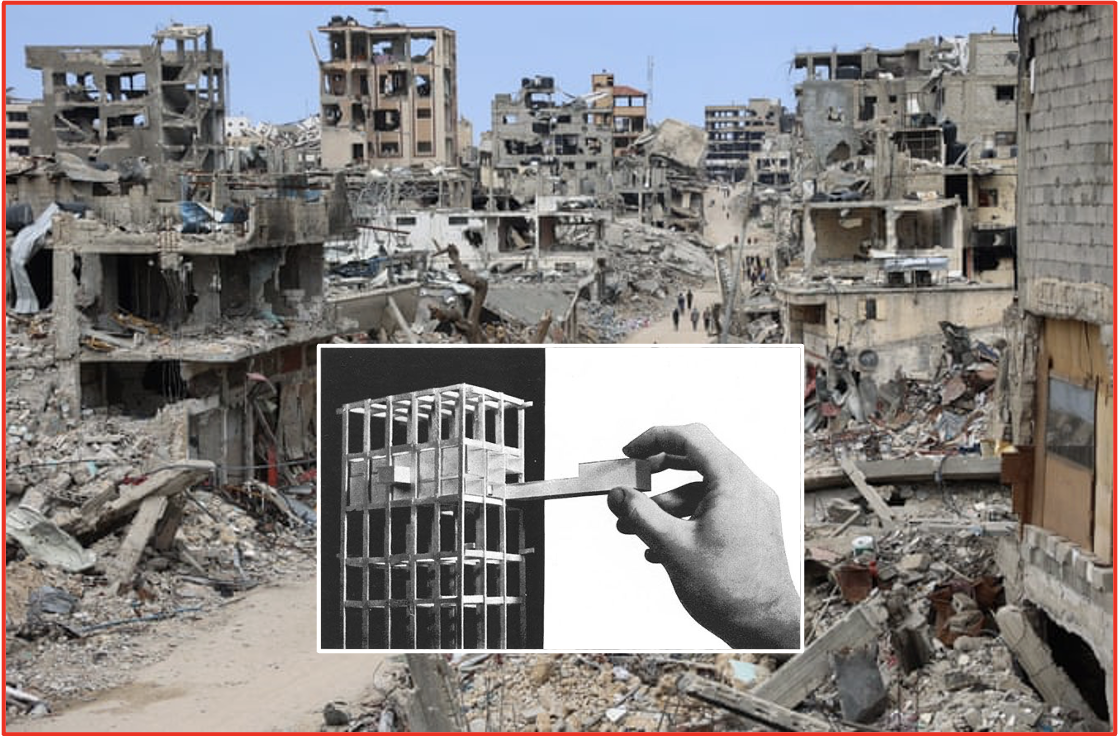

VS: This is a fascinating topic to me, at the heart of questions of style, appropriation, empire, conservatism, the sublime, and on and on. I’ve recently written about the function of rubble and ruins in shaping history, describing them as “memento mori of the built environment.”

Historically, they influenced responses to crisis precisely through their visibility, whether preserved as ruin or via reuse or image-making. The hypermediated visibility of ruination drove postwar reconstruction in Europe. In a different way, it also drove U.S. suburban sprawl, and U.S. interventionism after 9/11. However, something seems to have shifted in our current state of composite crisis, and the shift seems to be about visibility. As aggression, injustice, and ruination mount, so do efforts to obscure their consequences.

Realities are being rewritten and redrawn—often literally, through AI—and the signs of destruction that would ordinarily drive us to outrage, are harder and harder to source or distinguish from each other. This may not be just an outcome, this may be the goal: a program to distract us from the ruin. It was precisely this retreat from visibility that motivated my initial desire to formulate a class on this topic, and to engage with a group of socio-politically activated creative thinkers about it.

—

The Architecture and Crisis (AHIS 4270) course is scheduled to begin in the Fall 2025 semester, pending student interest and enrollment.

There’s still time to sign up—so don’t miss the chance to explore this timely and thought-provoking course. Students can register via the Self-Service portal on Navigator.