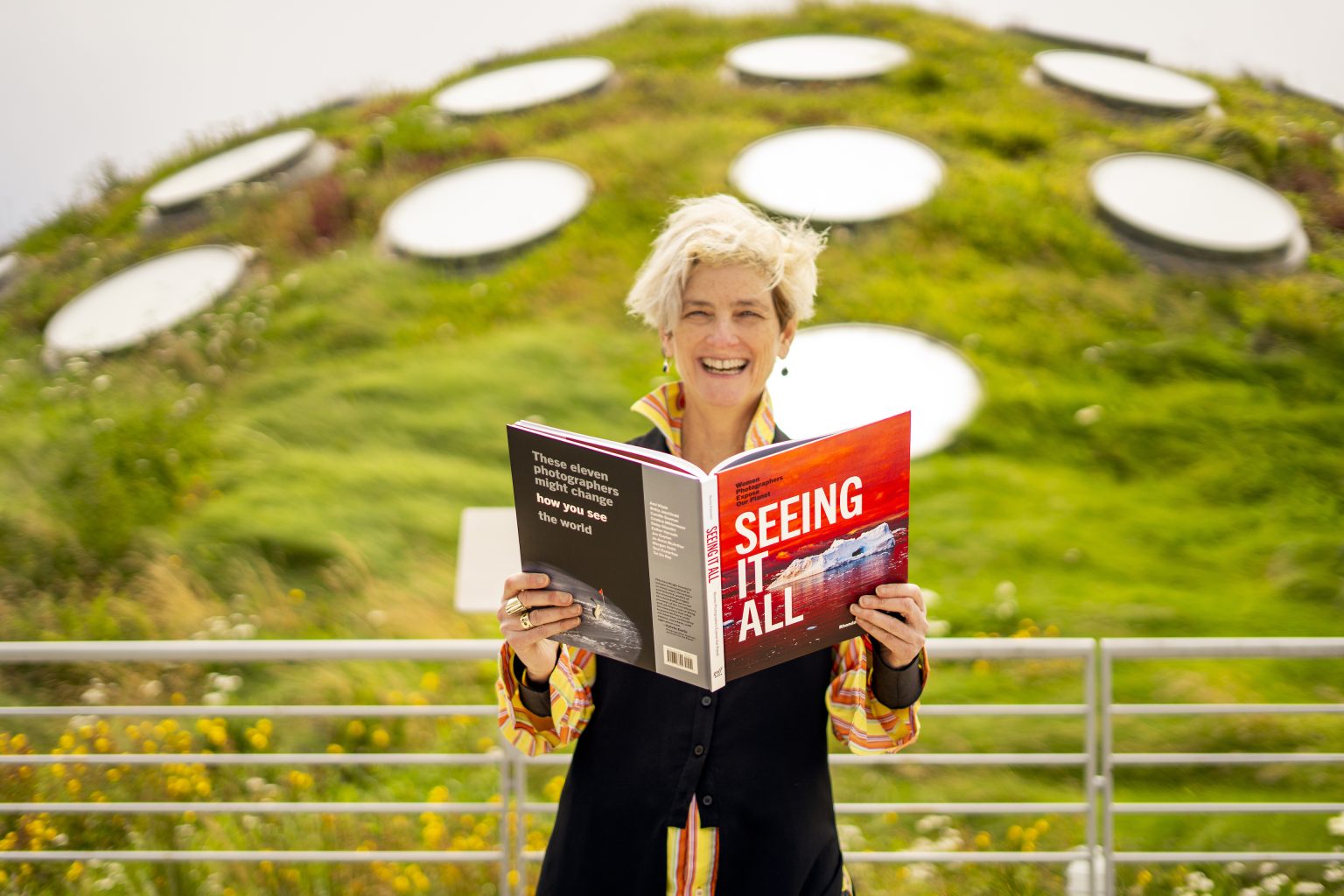

Rhonda Rubinstein (BDes ‘83) spent the 1980s and 90s working as a designer and art director at the likes of Esquire, New York Magazine, and Mother Jones—a time when magazines were cultural signifiers, conversation starters, and a stable career choice. It was also a time when the hiring process began by dropping off a physical portfolio at the publication office of your choice on its designated day and picking it up the next—which is how one week before she was set to leave the city, when her NSCAD exchange ended, Rubinstein wound up in the production department at New York. With the exception of a year working in Europe, she stayed in NYC for a dozen years before moving cross-country to work with the team behind Wired; now she is the Creative Director of the California Academy of Sciences, a science museum in San Francisco. Her new book Seeing It All: Women Photographers Expose Our Planet, “provides provocative perspectives on our relationship with the planet,” she says, “demonstrating what it will take to change our outlook and how photography can make a difference. Each of the 11 portfolios start with a statement that invites a different way of seeing the world.” It’s out September 1 and is available for pre-order.

How did you end up at NSCAD?

I saw the power of design in high school in Montreal. I found a class called Mass Media, possibly inspired by Marshall McLuhan—it was film, animation, advertising, design, journalism. It just fascinated me: the possibility of combining imagery, writing, design, typography.

My father took a job as head of the Biochemistry Department at Dalhousie as I was finishing Grade 11 and graduating high school. In Nova Scotia high school goes to Grade 12. I didn’t want to do another year of high school, but was too young to get into university, so I applied to NSCAD. NSCAD was more open-minded in terms of age requirements and, despite my minimal portfolio I was accepted. I was younger than most students, not even of drinking age. I still remember how tricky it was to get into Peddler’s Pub in those early years.

I started at NSCAD in 1979. The intro foundation class had thirty-some students and was taught by Tony Mann, an amazing teacher, who said ‘There are 30 of you in here and probably only 5 of you will graduate.’ It wasn’t a threat, it was just…this will be of interest for some, the rest of you will find different paths. And he was right, only a handful of us did graduate in Communication Design.

What was it like working in New York during the golden age of magazines?

It was exciting to be in the world’s media capital working on cultural stories that we thought were important. But I remember talking to someone at an industry event and saying that I had worked at Esquire during the golden age of magazines—they said ‘Oh with George Lois in the 60s?’ [laughs] I was somewhat offended that they thought I was that old. But the golden age is always 20 years behind you.

In George Lois’ time the art director had full reign over photo stories and conceptual covers, he convinced Andy Warhol to be seen drowning in a Campbell’s soup can. In the 90s when I was at Esquire, we used celebrities on covers to sell cultural ideas, but even then, the publicists oversaw the photo shoots and approved the cover selection. Still, there was some connection to the celebrity: ‘Robert Redford’s coming to the office to approve his cover!’ And it was still part of the cultural conversation where larger news and cultural issues were of concern to more people. Everything is much more fragmented now and targeted specifically to you. That context was so much fun to design in, where you felt like you were part of the larger conversation.

How did your environmental work start?

When David Peters and I started EXBROOK design, one of our first clients was The Ocean Conservancy; we developed a new magazine for them, called Blue Planet. We had a mix of publishing and business clients. Then we were hired to be creative directors for World Environment Day held in San Francisco in 2005—the first (and last) time it was held in the US! The theme was Green Cities, as that year the population had shifted, and more people were now living in cities. There were hundreds of events happening that week—we had to produce a website, a printed event program, highway billboards, street banners, newspaper ads, and badges and official credentials for the visiting dignitaries— it was a huge, huge project. Al Gore was one of the speakers, still developing his slideshow of An Inconvenient Truth. The transformation of the city and envisioning of what could be possible was the catalyst for me to want to work in that space.

You’re unfortunately always going to have work in that sector. Where do you see the impact design can have on environmental issues?

It’s tough. Right now, the problem is so interconnected and multifaceted and requires change at every level: government and industry and grassroots movements, in addition to what any individual can do. We are seeing the adverse effects of climate change every day (in the news). But I think about the impact design historically had on consumer culture— making products and ideas desirable to larger audiences. In the last half of last century, designers were proud of how they helped change perception (for businesses). Now I wonder whether design can make an alternative way of life and thinking just as desirable?

Let’s talk about your writing and curatorial work. Have you always had an interest in photography, and does it usually intersect with your environmental interests?

Yes, I have always had an interest in photography! When I was 12, I had a darkroom and wanted to become a photographer. And a significant part of my portfolio submission to NSCAD was photography. But when I started there, I appreciated how design combined the powers of photography and writing and pursued those studies. Fast-forward: At the California Academy of Sciences, I co-founded the BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition — which is celebrating its 10th anniversary this year! The idea is that photography is a unique medium for connecting people with the natural world. The intriguing photographs of wildlife and nature—and the conservation stories—really allow people to see what’s going on in the wilder world and get interested in animals and places they might not normally. More recently I collaborated with the Biosphere In Montreal— a museum of the environment— to produce a yearlong outdoor photographic exhibit on the theme of flow. Still / in motion showcases two great spectacles of nature playing out across the skies: icebergs in the Antarctic solstice and starling migrations in the English countryside.