Idleness is not a word that exists in Sarah Maloney’s dictionary. Whether she’s working on her next art installment, teaching at NSCAD University, helping students, or coordinating NSCAD’s Foundation program, this Nova Scotian artist, part-time faculty member, and NSCAD alumna (BFA 1988) is always on the move.

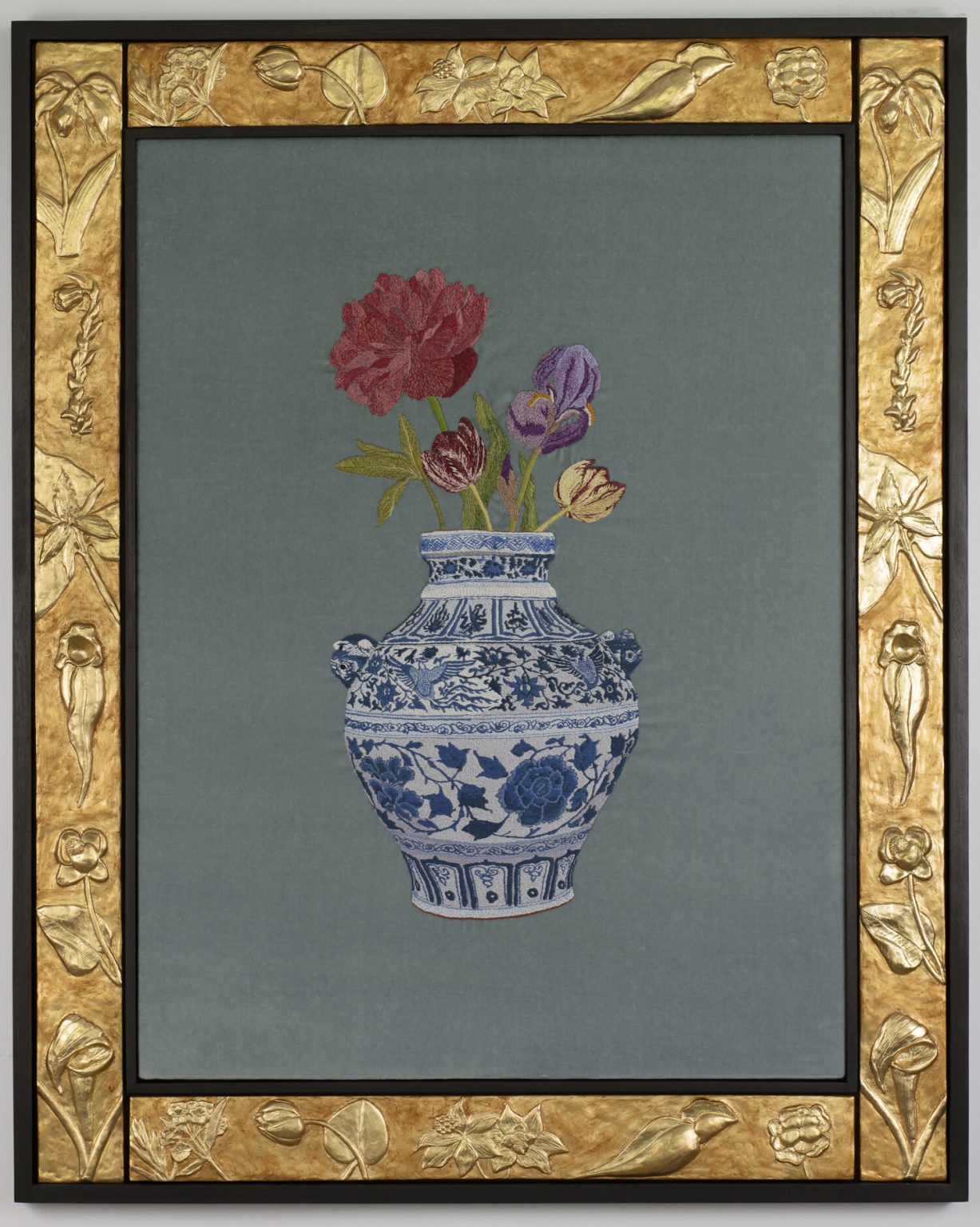

For Maloney, art can be found in every aspect of life — from the human body to daily domestic living. Her traveling exhibition, Pleasure Ground: A Feminist Take on the Natural World, blurs the lines between botany and anatomy, and draws back the curtain on the repetitive power of Mother Nature. Using metal, textiles, beadwork and embroidery, Maloney transports viewers to a wonderland of her own design, while simultaneously confronting the ideals of Western colonialism, art history, pleasure, and power.

Tell us about your journey as an artist and how you started in art?

If you go back to my second-grade report card, it says, “Sarah excels in language and art.”

Even in high school, I was taking as many art courses as I could. I would take art classes in the summer, go to museums, art galleries, and I had parents who were supportive. After high school, I went to Central Technical School in Toronto and did a three-year post secondary program, then I transferred to NSCAD to finish.

Eventually, I went to the University of Windsor to do a master’s degree and lived in Fredericton, N.B., for about eight years, where I started to build my career. I had my first solo show at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery there in 1999.

Right photo: ‘Lily’ is a bronze sculpture mounted onto an antique table. It depicts the flowers, leaves, stems, bulbs and roots of the plant.

Credit: Sarah Maloney.

What was it like having your first solo exhibition?

I was trying to get everything finished before the opening. I had a new baby at the time, and I remember having my party clothes on and still fixing something. That was the point in my life where the balance between being an artist, being a mother and having a job, was very challenging to do on some days.

What was it like trying to juggle motherhood, work and being an artist?

I think any woman who has to manage raising children — which is a full-time job — and working at anything else, is always feeling like something’s got to give every day; whether it’s the children who aren’t getting what they need, or the job, or the art practice. But actually, in the end, it’s the woman who isn’t getting what they need.

There’s a whole generation of women prior to me, who decided the only way you could be taken seriously as an artist is not to have children, or maybe have one child. On more than one occasion, I was questioned about my seriousness as an artist because I had three children. I think there’s this dichotomy in the art world where an artist is supposed to be completely selfish, while a mother is supposed to be completely selfless. For some reason, nobody can get their head around the idea that you can put those things in boxes.

Can you tell us more about the art works in your Pleasure Ground exhibition?

The artworks were created over the course of 30 years; the first piece was made in 1993 when I was in grad school, and the last ones were made in 2021 during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Initially, my research was about the body and how the body has been represented historically. So, you’ll see knitted bones, knitted brains, beaded skins, and embroidered bodies in this exhibition. But then there was a transitional period, when I was an artist in residence at the Memory Disability Clinic at the Camp Hill Veterans Memorial Hospital. During that year, I looked through historical medical illustrations and found drawings of body parts, and how they’d been rendered looked much like botanical forms.

So, I started to play with that dichotomy of forms repeating in nature: how cells grow, how bodies are built, and how plants are built. From there, I took a leap to work with only flowers and used floral forms to stand in for the body. At first, I didn’t trust it because drawing flowers were always considered feminine; even the plants themselves had feminine Greek or Latin names. However, it gave me the inspiration to make ‘Collapse,’ which talks about many things including, notions of women’s hysteria.

What is the feminism aspect of your work?

A lot of my work has important historical references and look into issues of the domestic space. What I’ve seen over the years from my time as a teacher is we tend to have a majority of female or female-presenting students in art schools. But then you look at the art world and the market where the expensive stuff is in terms of collections, galleries, auctions, and dealers, and all of that is still male-dominated.

There’s this sense that the kind of work-life balance that most women achieve as artists, takes them out of that kind of high-end competition. But then we need to ask ourselves, who’s controlling the money and who’s buying those things. For me, the feminism of all of this is trying to understand the role women have had, continue to have, and may have in the future when it comes to art.

Do you have any words of advice to young and emerging female artists out there?

Make what you believe in. Keep working and be committed to your work. You can’t try to second-guess what the market is looking for or what curators want, you just have to believe in your vision and work at it. Be rigorous, get feedback, talk to people and apply for everything, but you really just have to put in the work.

—

Sarah Maloney’s Pleasure Ground: A Feminist Take on the Natural World is currently exhibited at the Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, until June 1, 2024. To see more of her work, visit her website.